Yields up, pound down

UK GOVERNMENT BONDS ARE UNDER PRESSURE, SENDING BORROWING COSTS ROCKETING ONCE AGAIN. BUT IT’S NOT ONLY BRITAIN THAT’S AFFECTED, AND IT MOSTLY STEMS FROM ACROSS THE ATLANTIC.

The American economy has run hot for a long while now. Apart from a dip in the first half of 2022 and a slight slowdown in the first quarter of 2024, annualised GDP growth has remained above 2% each quarter following the COVID recession. In the most recent two quarters, the economy has been on pace for more than 3% annual growth.

That’s exceptional. Since the beginning of 2023, the Eurozone has managed a pace of growth that would only achieve between 0% and 1.6% a year, while the UK had a recession in the second half of 2023 and a short-lived rebound in 2024 that has already melted away. Chinese growth – if the numbers are to believed – is just half a percentage point or so ahead of the US over the past couple of quarters!

For quite a while, many people have expected knock-out American growth to ease back towards 2-2.5% as the effects of Biden-era government spending wear off. At that pace, there would be less chance of an overheating economy reigniting inflation and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) would be able to continue cutting interest rates. Lower borrowing costs ease the strain on indebted households and businesses and boost the values of stocks and bonds, all else being equal. Instead, the US has continued to barrel along, adding lots more jobs than expected. Just last week the US reported almost 100,000 more roles had been created than forecast, sending the unemployment rate lower to 4.1%.

The next US CPI inflation report is released this week and is expected to rise for the third consecutive month, from 2.7% to 2.8%. The US Fed favours a different measure of inflation than the CPI that most nations use: core PCE, which includes shelter and removes volatile food and energy prices. This measure already hit 2.8% recently. And this is all before Donald Trump returns to the White House (he takes office on the 20th of this month). His policies seem more likely to worsen inflationary pressures than stymy them.

As Trump’s inauguration has approached, hopes have steadily faded for cuts to the Fed’s overnight interest rate. Only in September, investors believed this rate would be 4.0% by July this year. Today, they think it will be 4.3%, which means just one more quarter-percentage-point cut is expected in the next six months, and maybe not even that. That has had two effects: the first is that US government bond yields have risen dramatically. The 10-year has moved from 3.8% three months ago to more than 4.8% today (so the price of these bonds has fallen substantially). The second is that the value of the dollar has gone higher as well because the higher risk-free return from keeping your money overnight at the Fed has attracted more investors to the US.

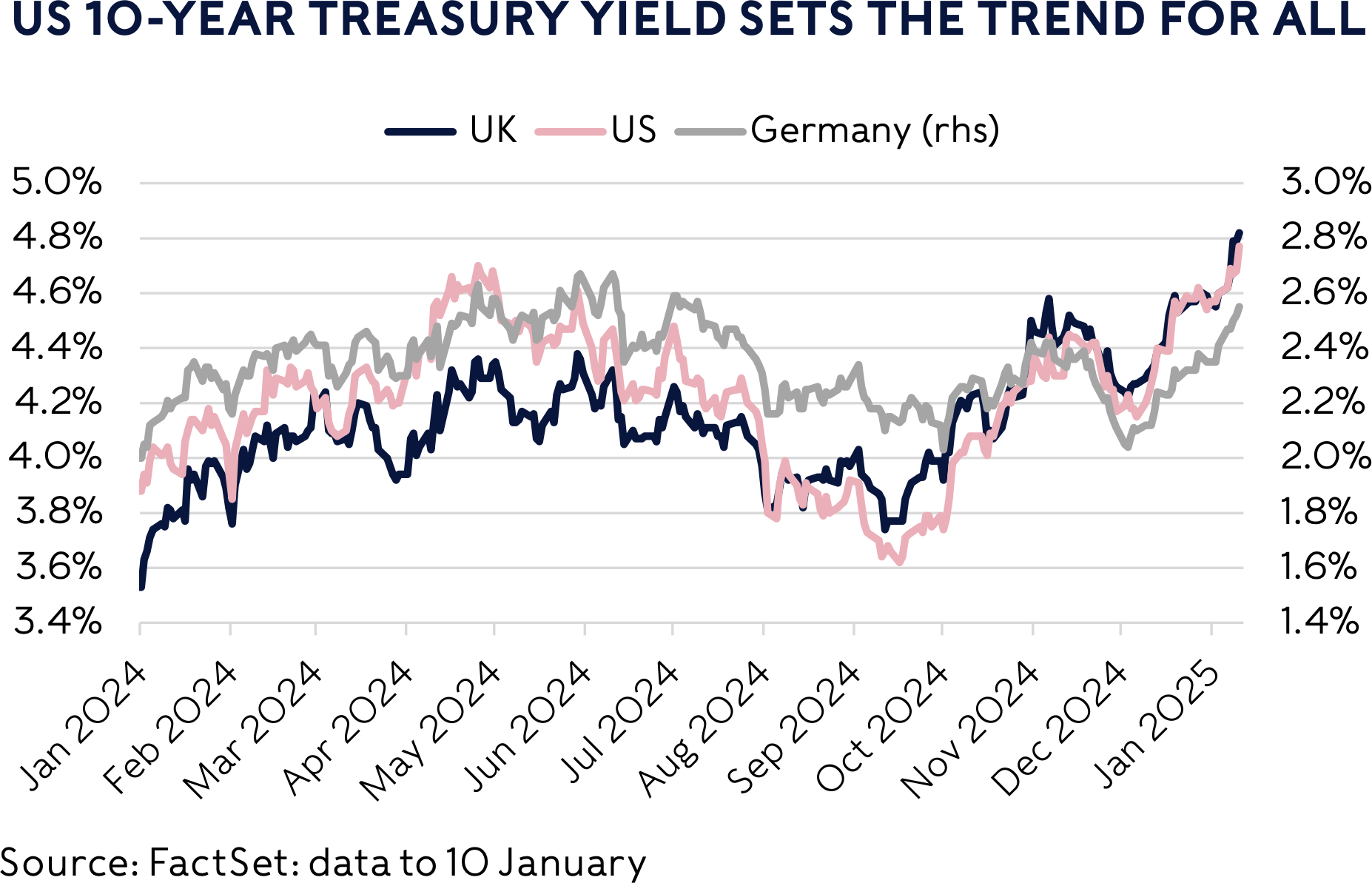

The US 10-year yield is the most important rate for valuing investments, regardless of where you live or where you invest. It is the bedrock for all the other, local rates. When it moves, virtually all others do too. This is the predominant reason why UK government bond yields have risen rapidly in recent months to multi-decade highs. You can see in the chart above that even the German bond yield has risen along with the UK and US, despite Germany having none of the concerns on public finances that have been much discussed here and in the US in recent weeks.

Not so sterling

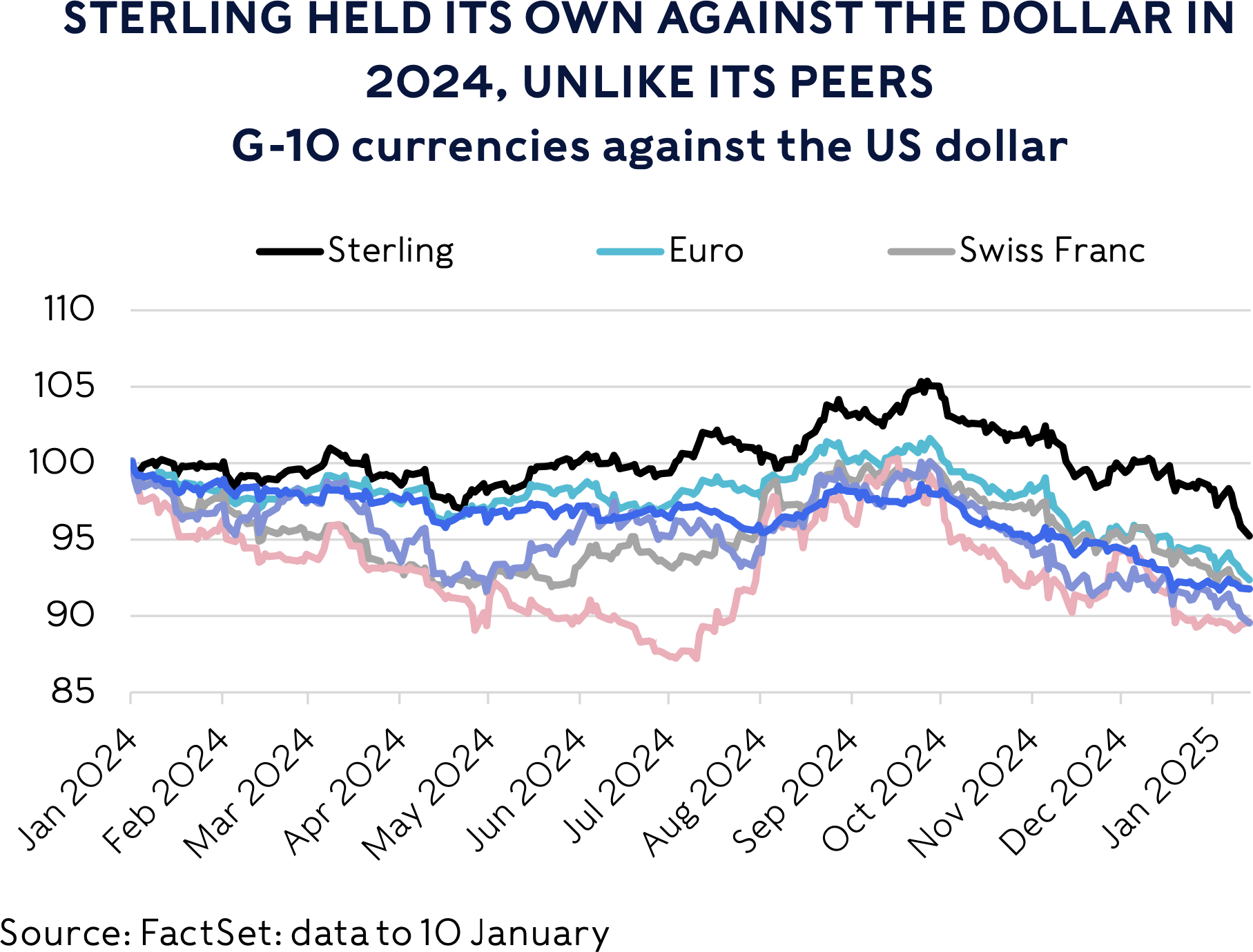

Another potential reason for the wave of sales of UK government bonds is because – unlike most other major currencies – the pound actually held up relatively well against the dollar last year. So in early 2025, as US yields rose and the dollar strengthened against sterling (and every other major currency), foreign investors likely saw the pound as overvalued and got out. In fact, most other G-10 nations’ currencies have also fallen in value in recent weeks, albeit not by as much.

But when the currency falls, that should make the pound more attractive to foreign investors. It’s a sort of equalisation mechanism of floating exchange rates – it’s a feature, not a bug. In the past, UK bond yield spikes and currency crises have tended to happen because the government was trying to peg the currency at a value that foreign investors thought was too high: the classic case in point being the unsuccessful peg to the Deutsche mark in the early 1990s. That’s not the scenario we’re faced with today.

UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s economic policies leave a lot to be desired right now, no doubt. But unless she is also the US Treasury Secretary, or the Treasury Secretary for the whole of the western world, then there’s no way she’s causing this rout. It’s been many decades since Westminster was powerful enough to have that much influence on global rates! This is empirically different to the Truss/Kwarteng gilt crisis of 2022, when the 10-year gilt yield surged by more than 1.1 percentage points in just three days while global rates were relatively stable.

One thing to note is that about one-fifth of the rise in gilts does seem to be due to increased investor concerns about the risks for the UK specifically, likely fiscal worries as GDP growth slumped to 0% in Q3 and the extra borrowing costs erode the headroom between the Exchequer’s expected tax revenue and projected costs.

All of this doesn’t mean that much higher borrowing costs aren’t a big problem for the UK government! Just as for indebted households and businesses, they are extremely unwelcome. But it’s only a problem if yields stay this high. If US central bank interest rates fall back, as most investors expect, then you would expect UK yields to recede with them. Yield spikes have caused angst about UK government finances several times over the past five years, only for the problem to melt away when panic subsided taking yields with them. Let’s hope the same happens this time as well. If not, greater borrowing costs may force the government to tighten policy to meet its fiscal rules. It’s got until 26 March when the Office for Budget Responsibility gives its verdict on the rules – bond yields could easily move another half of a percentage point (in either direction!) between now and then.

The views in this update are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions and are current as of the date posted. While all material is deemed to be reliable, accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed.

This document was originally published by Rathbone Investment Management Limited. Any views and opinions are those of the author, and coverage of any assets in no way reflects an investment recommendation. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and you may not get back your original investment. Fluctuations in exchange rates may increase or decrease the return on investments denominated in a foreign currency. Commissions, trailing commissions, management fees and expenses all may be associated with mutual fund investments. Please read the prospectus before investing. Mutual funds are not guaranteed, their values change frequently, and past performance may not be repeated.

Certain statements in this document are forward-looking. Forward-looking statements (“FLS”) are statements that are predictive in nature, depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “could,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “intend,” “plan,” “believe,” or “estimate,” or other similar expressions. Statements that look forward in time or include anything other than historical information are subject to risks and uncertainties, and actual results, actions or events could differ materially from those set forth in the FLS. FLS are not guarantees of future performance and are by their nature based on numerous assumptions. The reader is cautioned to consider the FLS carefully and not to place undue reliance on FLS. Unless required by applicable law, it is not undertaken, and specifically disclaimed that there is any intention or obligation to update or revise FLS, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.